Seven Million Fish?

March 31st, 2017Tuesday morning’s adult field trip to English Turn turned out to be way cooler than I thought. As an admirer of collections and collectors, I hit the proverbial jackpot. Fish!

Rows and rows of metal shelves are lined with over 200,000 glass jars full of fish.

Tulane University Biodiversity Research Institute (TUBRI) has the world’s largest post larval fish collection– over 7 million fish specimens, the Royal D. Suttkus Fish Collection. These fish are in glass jars of liquid on metal shelves in a curated space in an abandoned military bunker next to the Mississippi River on the West Bank in Plaquemines Parish.

(That might have been a personal record for sequential prepositional phrases.)

Over 200,000 jars line metal shelves in a retired ammo bunker near the Mississippi River in English Turn. Look past the glass jars to get a sense of the depth of the room.

You might wonder, who needs 7 million fish?

Well, we do. We can use these specimens to learn about climate change.

Over 7 million specimens sit in museum quality glass jars.

Get this: fertilizers applied to farmland in the upper midwest run off into streams that eventually enter the Mississippi River. Forty-one percent of the nation’s water ends up flowing through the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico. As the water enters the gulf, the heavy sediment drops. The water clears a bit. The fertilizer causes a huge growth of algae. The algae dies, sinks, and robs the water of oxygen. Fish are able to move away from hypoxic areas, but invertebrates go into a state of shock. Imagine a tired worm, couch-potato style on the bottom of the gulf. That worm becomes an easy target by certain groups of fish who can swim in and swim out of hypoxic areas, snacking on those tired worms. The fish grow and thrive, while other specimens don’t— and we can study those changes because of collections like this one held by TUBRI, comparing past specimens to present ones.

Startling fish specimens look out from glass jars at TUBRI in English Turn.

The folks at TUBRI are tasked with, among other things, maintaining the specimens and collecting more. Royal D. Suttkus, the scientist who previously curated the collection, and for whom the collection is named, is responsible for a large percentage of those 7 million fish. I asked the current TUBRI Director, Henry L. Bart, Jr., Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, how often he fished.

“You mean, sample?”

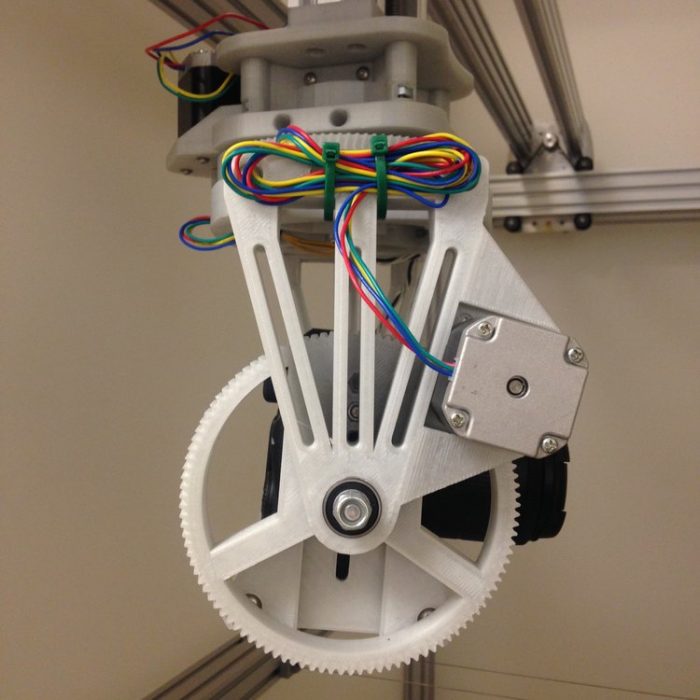

Turns out, not much. TUBRI is leading the charge on geolocating, digitization, and providing remote access to their archives of fish by using technology to create time and space. That means people can study a 3-D image using fancy machinery they built that takes over 200 photos of a single specimen in a very short amount of time (to limit the exposure to air). This isn’t just fish— it’s technology, engineering, craftsmanship, journalism, investigation, photography, communication, AND science— all of this taking place at a dead end gravel road in a former ammo bunker just outside the city, eventually providing access to scientists around the world.

A new toy at TUBRI was built to photograph fish specimen. These machine parts are 3-D printed, loaded with cameras, and set to take over 200 images that will be strung together to create a model that can be used for remote access to the largest fish collection in the world.

This is evidence of what we mean when we say new harmonies— the creating of new work, new combinations, new ways of thinking about studying and understanding our coast and climate and what’s happening under the surface of the water, from our past to our present, to the ways our New Harmony High students will impact the future of the Louisiana we love.